Building Open Recommendations

A full breakdown of how I built Open Recommendations, the inner workings, the choices I made, including provider agnostic AI, strict data structures, deciding whats a recommendation and whats just an observation, RAG, and weighting community feedback.

I'm not sure if you've noticed, but there is a lot of buzz around AI; why you should/must use it, how it can save time/do everything, how it will destroy the world. So let's get this out the way first.

Yes I will be talking about AI, but there will be no hype or hyperbole here. I will be explaining what and how we've used AI in building Open Recommendations as a way of explaining how I think about the use cases, the advantages and disadvantages of certain approaches, and how I approach it from a data point of view. It will be practical and a bit technical but it will be grounded I hope.

What is Open Recommendations?

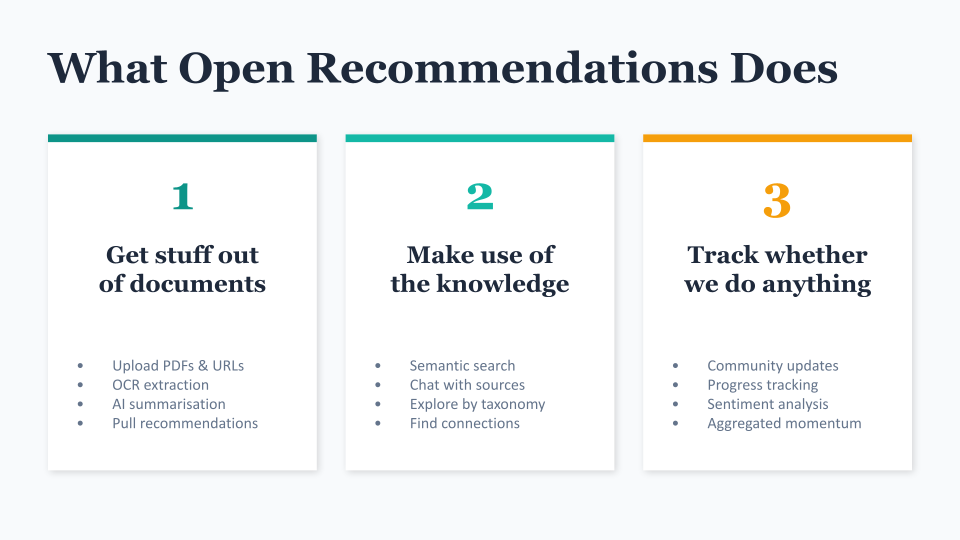

It's designed to be a central hub to upload, analyse, and track reports and recommendations across the social purpose sector. In its most simple form it:

- allows users to upload a 'source' such as a report via either a document or url

- extracts the source into a machine readable format

- summarises and categorises against a taxonomy

- pulls specific recommendations from the source

- categorises these recommendations against a taxonomy

- allows the searching, exploration and chatting with the knowledge base created

- allows community based tracking of action towards recommendations

Or in more simple terms:

- Get stuff out of documents

- Make use of this knowledge

- Track whether we actually do anything about all the recommendations we make

You can read more about the why of Open Recommendations here.

Making use of AI

So yeah I use LLMs in Open Recommendations and what I wanted to do here is break down how I've used them, as maybe a helpful guide to others if they are thinking about exploring this stuff. As mentioned there is a lot of stuff written about AI and I find that in the social purpose sector especially we give a very minimal amount of actual detail of what this actually involves. Or if we do give detail it is very technical. I also want to lay out some of the choices I've made along the way and why I made them. So I'm going to try to strike a balance here between giving enough detail without getting too technical.

As I broke down earlier, there are various things that Open Recommendations does. From an AI point of view this can be explored in two main parts: getting stuff in, and making use of the stuff once it's in.

AI ingestion (getting stuff in)

So one of the things we think is useful on Open Recs is the ability to upload a source in the form of a document, which in many cases is a pdf. Now I could write a whole post about the dreaded pdf, but let's face it, it's still the most used format for documents. We also allow users to point to a url if they have a source that is HTML which is a much simpler process, so we'll leave that for now.

When a user uploads a pdf we do the following:

- Firstly we store that pdf as is

- Then we use an OCR to fully extract everything in it - text, data tables, links - into a machine readable format (markdown) and store this making it possible to fully recreate the pdf but in a more usable format.

- Once we have the full extract we use an LLM to create a summary of the source and categorise it (by source type, purpose, thematic area, role relevance) and store these

- We then create an embedding of this information

- We then extract specific recommendations contained within the source

- And then we categorise those recommendations (purpose, target audience, thematic area, location scope)

- Finally we create an embedding of each recommendation

So there's a lot going on here, but to a user it's simply click upload and await the return to check and make any edits if they choose to. I chose to split these processes up for a couple of reasons.

Firstly from a technical point of view this allows independent scaling - if recommendation extraction is slow, we can optimise that without touching the OCR step. But more importantly, it means we can swap components in and out. This becomes really important when we talk about AI models.

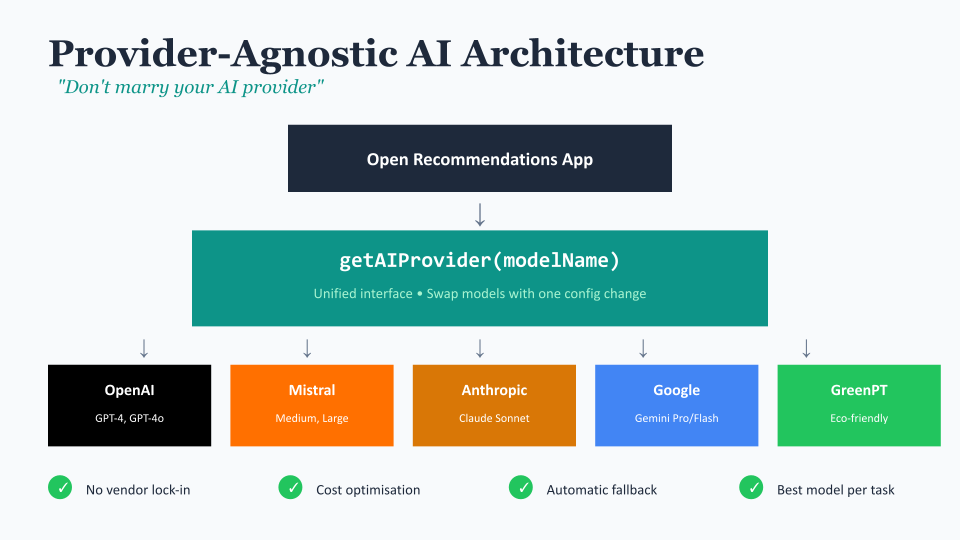

The "don't get too attached to your AI provider" principle

So, in case you hadn't noticed, AI providers are not stable partners. Pricing changes, models get deprecated, service goes down, and suddenly that OpenAI dependency you built your whole system around becomes a problem.

So I built Open Recommendations to be provider-agnostic from day one. It currently support over 19 different AI models through a unified interface - Mistral, OpenAI, Anthropic (Claude), Google Gemini, and even some more niche options like GreenPT for those concerned about environmental impact.

The way this works is fairly straightforward. We have a single function that takes a model name and returns the right provider configured correctly. When we need to make an AI call anywhere in the system, we call this function rather than directly calling OpenAI or whoever. If tomorrow we decide Claude is better for a particular task, we change one configuration value. If Mistral doubles their prices, we switch to Gemini. No rewriting of business logic required.

This isn't just about hedging bets though. Different models are genuinely better at different things, and this architecture lets us be intentional about that.

Different models for different jobs

This is where it gets interesting. Not all AI tasks are created equal, and treating them as such is both wasteful and often produces worse results.

Take our OCR step. When we're extracting text from complex PDFs - ones with tables, multiple columns, embedded images - we need something that can actually see the document. So we use vision-capable models here, specifically Mistral Vision or Google Vision depending on the document complexity. A pure text model simply can't do this job.

But when we're summarising that extracted text? We don't need vision capabilities. We need something good at understanding context and producing coherent summaries. Here a model like Claude or GPT-4 Turbo excels.

For the recommendation extraction, we need something that can follow fairly complex instructions reliably - identifying what is and isn't actually a recommendation (more on this shortly), categorising against multiple taxonomies, and outputting in a very specific format. This is where model choice really matters, because consistency is everything.

And for the embedding generation - turning text into numerical vectors for search - we use a completely different type of model altogether. These embedding models are specifically trained for this task and are much cheaper to run than the big language models.

The point is: matching the model to the task saves money, improves results, and means you're not paying GPT-4 prices to do work that a smaller model handles perfectly well.

Making AI play nice with your data (strict structures)

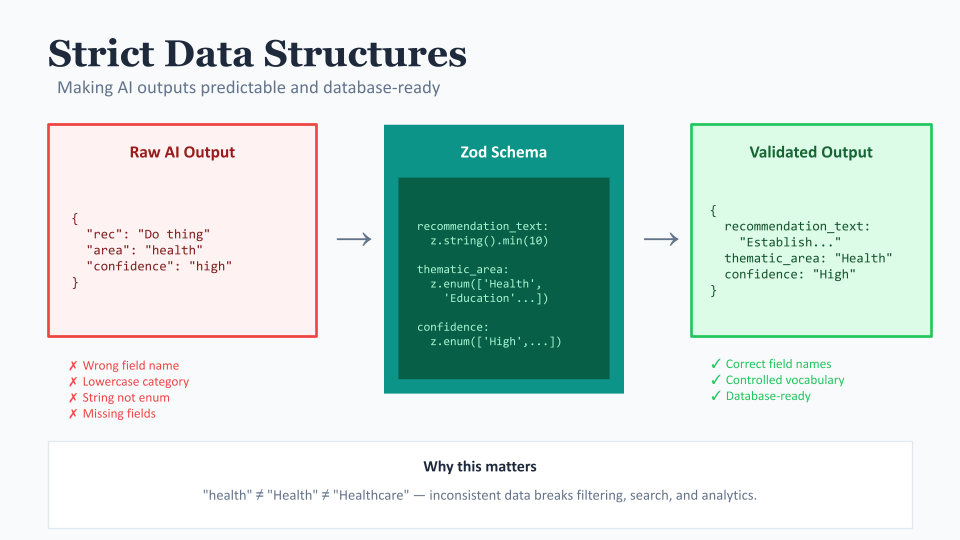

The most consistent thing about LLM's is that they are not consistent, they're unpredictable. Ask the same question twice, you might get differently formatted answers. Ask it to return JSON and it might wrap it in markdown code blocks. Or not. Or add a helpful introduction before the JSON that breaks your parser.

This is a massive problem when you're building a system that needs to actually do something with the AI's output. We need recommendations in a specific format so we can store them in our database, search them, categorise them. "Close enough" doesn't cut it.

So we use something called schema validation to define exactly what the AI's output must look like. When the AI returns something, we validate it against this schema. If it doesn't match, we reject it and try again (or handle the error gracefully).

For example, a recommendation must have a recommendation_text (string), a target_audience (from a defined list), a thematic_area (also from a defined list), a confidence_score (High, Medium, or Low), and so on. If the AI decides to get creative and return something different, our system catches it.

This sounds pedantic but it's absolutely essential. Without it, you end up with data quality issues that compound over time. One recommendation stored with thematic_area as "health" and another as "Health" and another as "Healthcare" - suddenly your filtering and analytics are broken.

We also use controlled vocabularies for our categorisation. Rather than letting the AI free-text categorise things, we give it a specific list: "The thematic areas are: Health, Education, Environment, Housing, Employment..." and so on. The AI must pick from this list. This means our data is consistent and our filters actually work.

Not everything is a recommendation

One of the more interesting challenges was teaching the AI what actually constitutes a recommendation. Turns out a lot of text that sounds recommendation-ish... isn't.

Consider these three statements from a typical report:

- "The sector needs significant improvement in data sharing practices"

- "Many organisations struggle to secure long-term funding"

- "Local authorities should establish dedicated funding streams for community organisations within the next 18 months"

Only the third one is actually a recommendation. The first two are observations or statements of the problem. A recommendation needs to be actionable and prescriptive - it should have someone who needs to do something, and ideally a sense of what and when.

We train our extraction prompts to look for imperative verbs (establish, develop, implement, create, ensure), clear target audiences, and actual calls to action. We also assign confidence scores - if it looks like a recommendation but we're not sure, we mark it as low confidence and the user can review.

This filtering is crucial. Without it, you end up with a database full of "recommendations" that are actually just problems restated. Not useful when you're trying to track action.

This training is an ongoing process and we don't always get it right. What we have noticed is that people write in a lot of different ways and are often not explicit in recommendations. There are probably many reasons for this, but it makes it hard, for both humans and especially non-humans to fully pick the intention.

Making use of the knowledge (search and chat)

Once we've got all this structured data, the next challenge is making it useful. This is where embeddings come in.

An embedding is essentially turning a piece of text into a list of numbers - a vector - that represents its meaning. Similar texts will have similar vectors. This means we can do semantic search: find recommendations that are conceptually similar even if they use completely different words.

So if someone searches for "climate action in schools" we can find recommendations about "environmental education programmes" or "reducing carbon footprint in educational settings" - things that are clearly relevant but don't contain the exact search terms.

We combine this with traditional keyword search (sometimes you do want exact matches, like a specific organisation name) and the result is a hybrid search that handles both use cases.

The chat interface builds on this. When a user asks a question, we:

- Turn their question into an embedding

- Find the most relevant sources and recommendations

- Feed those to an AI as context

- Generate a response that's grounded in the actual content

This is called RAG - Retrieval Augmented Generation - and it's the difference between an AI that makes things up and one that gives you answers based on actual evidence. The AI can only draw from the sources and recommendations we've given it, and we show the user which sources informed the answer. We think this is why Open Recommendations is better/different than more generalised chat interfaces.

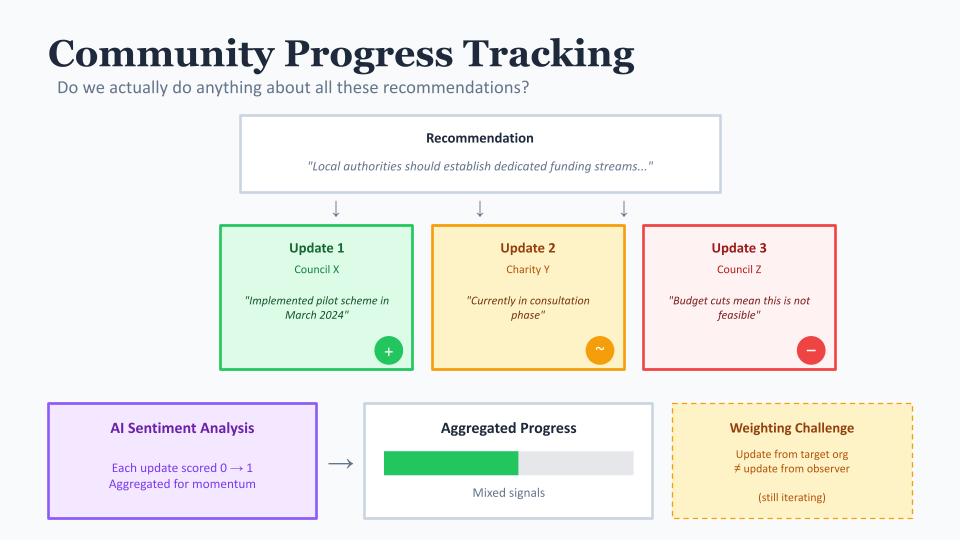

Tracking progress (do we actually do anything?)

This is perhaps the most important and least glamorous part of Open Recommendations. We make a lot of recommendations in this sector. We commission reports, hold consultations, conduct evaluations. And then... what?

Open Recommendations allows community-based progress tracking. Anyone can add an update to a recommendation: "We've started work on this", "This was implemented in our area", "This was rejected because...". Each update captures who made it, when, and crucially - a sentiment score.

The sentiment scoring was an interesting design challenge. We wanted to capture not just "has this been done or not" but the nuance of progress. Is this update positive movement? Negative? Neutral? We use AI to analyse the update text and assign a sentiment score from 0 to 1, which we then aggregate to give an overall sense of momentum on a recommendation.

This creates a kind of community evidence base. If ten organisations all report that a particular recommendation is impractical, that's valuable information. If one area has successfully implemented something, their experience can inform others.

The challenge here is weighting. A progress update from the organisation named in the recommendation probably carries more weight than one from a random observer. We're still iterating on how best to represent this, but the principle is that tracking should be community-owned, not gatekept.

What I've learned

Building Open Recommendations has reinforced a few beliefs I had and challenged others.

The biggest reinforcement: AI is a tool, not magic. It's very good at certain things (extracting structured information from unstructured text, understanding semantic similarity, generating contextual responses) and poor at others (being consistent, knowing what it doesn't know, handling edge cases gracefully). The skill is knowing where to deploy it and where to keep humans in the loop.

The biggest surprise: how much of the work is not the AI part. Data modelling, validation, error handling, user interface, privacy controls - the AI is maybe 20% of the actual system. The other 80% is all the boring stuff that makes it actually usable.

And the ongoing learning: the right architecture matters enormously. The decision to make the AI layer swappable has already paid for itself multiple times as I've optimised costs and performance. If I'd hardcoded OpenAI calls throughout the codebase, we'd be in a much harder position now.

In closing

If you're in the social purpose sector and thinking about building something with AI, I hope this has been useful. The technology is genuinely capable of things that would have been impossible a few years ago. But it needs to be approached with clear thinking about what you're actually trying to achieve, what the AI can realistically do, and how you'll handle it when things go wrong.

Open Recommendations isn't finished - it's still being developed and improved. But the foundations are solid because we took time to think through the architecture rather than rushing to bolt AI onto something.

If you'd like to try it, learn more, or get involved, you can find Open Recommendations at https://www.openrecommendations.com/. And if you've got questions about anything I've covered here, I'm happy to go deeper - just get in touch.